Recently I received this invitation from a great website to share the blog below on ocean rubbish from Morgan Matus.

This being an issue close to my heart and also coinciding with a number of other organisations and initiatives ongoing and emerging (including, BeachCare and the Ocean Friendly Design Forum, the RSA Great recovery Re-conference on plastic ), I’m happy to share it with you here.

It is written primarily for an American audience so some of the activities or organisations may not be the same as in the UK. However, interestingly since this really is a globally interconnected issue you do find that a lot are just as relevant and take on a global approach, perspective towards this issue. You can link back to the original at Fix – A Sea Full of Trash .

Tackling our plastic problem

Beyond the landfills and trash heaps moldering in almost every town and city across the globe, manmade garbage has found its way into the natural landscape on a mind-boggling scale. It seems as though there are virtually no places left on Earth free of our rubbish. Junk can be found everywhere – from the bellies of animals and the tissues of our own bodies to the world’s vast oceans.

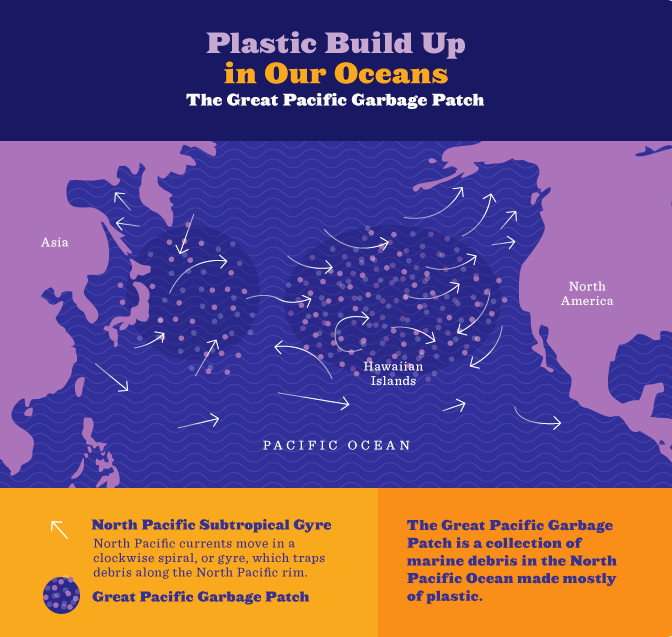

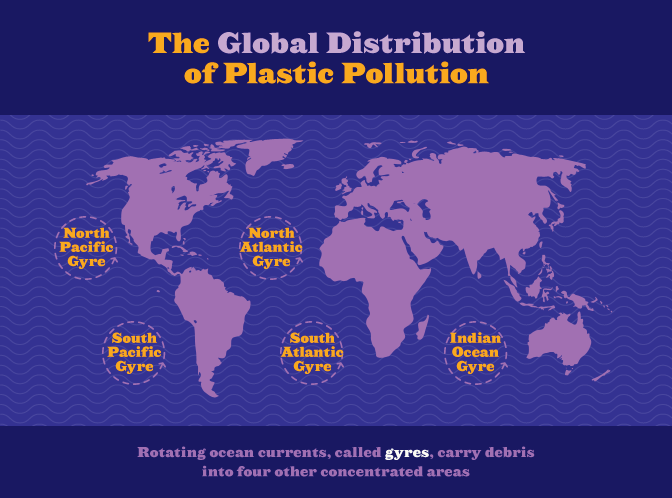

The gigantic mess currently swirling around our oceans is ever-growing. There are so many manufactured items floating around the briny deep that marine currents have formed sprawling expanses of crud in the water. One of the most disheartening of these disasters is known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch; a field of debris formed by wind and wave action and discovered by Captain Charles Moore in 1997. While there are no literal islands of trash, the vortexes are gargantuan concentrations of waste located in two major areas, with one midway between Hawaii and California and another off the coast of Japan. The overall amount of debris is still unknown, but scientists estimate the entire Patch encompasses nine million square miles of watery real estate, and is just one of five major garbage clusters occupying the world’s oceans. A majority of this pollution is made up of plastic, leaving scientists scrambling to invent methods to remove the non-biodegradable hazards.

Source: Fix.com

Source: Fix.com

During the 20th century, synthetic plastics became the material of choice for industries from consumer packaging to fashion. Practically indestructible and with the ability to mold into virtually any shape, plastic polymers could withstand the elements and remain intact longer than their organic counterparts. With plastic, perishable food could be transported and preserved longer, electronics insulated and made more efficient, and medical supplies kept sterile and disposable. Unfortunately, the physical tenacity that makes plastics so desirable as grocery store packaging or dishware also creates a gigantic problem for the environment. Most plastics produced today are formed from petrochemicals, which means it takes an enormous amount of time for each straw, water bottle, and single-use fork to break down and disappear. To make matters worse, extracting oil as a basis for these textiles adds fuel to the global warming fire by sustaining a demand for fossil fuels and toxic contamination.

So how do we halt the spread of plastic into the sea and remove what is already there? The first step toward keeping trash from entering the ocean is to reduce the amount created on land and repurpose what we chuck into trash bins.

Unfortunately, there are very few large-scale projects able to tackle the magnitude of our plastic predicament. To begin with, plastic manufacturing companies have little incentive to switch from oil-based polymers to more sustainable, biodegradable options, or to use recycled material. This is in part because it is still cheaper to produce items out of raw, fossil-based feedstock. The major forces driving the conversion to corn, potato, or soy bioplastics come primarily from consumer demand and regional campaigns in cities like Los Angeles and Concord, Massachusetts, where there are efforts to ban plastic bags and water bottles.

Source: Fix.com

Even if synthetic plastics were outlawed altogether by every nation on Earth, the challenge of removing what is still suspended in the ocean would remain a major dilemma. Scientists are just beginning to quantify the amount of plastic hanging out in the water column, how sunlight breaks down large pieces into smaller fragments called “microplastics,” and in what way these bits affect the food chain. The plastic can block sunlight from reaching algae and, in turn, negatively affect organisms that feed on this most basic and important level. Humans rely on that food chain for survival, so plastics (and the hazardous chemicals they contain) can eventually damage our dinners and poison our ecosystems.

To put oceanic plastic into perspective, consider this: In a 2014 study expedition conducted by the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, a sample from a one-hour trawl 260 miles from the center of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch pulled up thousands of times more plastic by weight than plankton, meaning that more synthetic materials were present in one scoop of seawater than the animals that are supposed to live there. Deep-sea explorers such as those working with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Institute in California were amazed to find crud thousands of meters down with a full third of the messy makeup consisting of plastic. Not just eyesores, the materials concentrate dangerous chemicals and act as sponges for toxins such as DDT, PCBs, and PBDEs.

A Solution for Synthetics

As researchers struggle to understand the scope of the situation, local governments, non-profits, and universities are working on a host of creative solutions. Since the physical problem is situated far from the jurisdiction of any one nation, the responsibility to find a fix seems to have fallen on committed organizations and stewards of the environment. Most focus on land-based initiatives such as The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s regional action plans that coordinate cleanups around the U.S. through their Marine Debris program. The agency is also working with the fishing industry and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation to reduce the damage done by derelict fishing gear.

Prototypes for marine robots – such as the Veolia Drone developed by French International School of Design student Elie Ahovie or the Protei invented by Cesar Harada – could one day scour the ocean for trash. Larger groups that employ booms and filters, like the Ocean Cleanup system proposed by entrepreneur Boyan Slat, could be placed in areas of concern to help trap trash. However, most of these technologies are still firmly situated on the drawing board, and have not adequately addressed logistics (like how the machines would determine the difference between tiny bits of plastic and living critters of a similar size). They would also have to be durable enough to withstand the destructive effects of seawater, storms, and physical stress.

In recent years, scientists have observed various species of bacteria colonizing rafts of plastic debris, making up what they have dubbed the “plastisphere.” Scanningelectron microscopy from researchers at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution revealed thousands of organisms creating an almost reef-like ecosystem on the surfaces of floating flotsam. It is still a mystery how the byproducts of their digestion affect the rest of the ecosystem. Bioengineers have proposed manufacturing bugs that could act in a similar way to their naturally occurring relatives to mop up the mess, both on land and sea. But releasing any new element into an incredibly complex web of life carries enormous risk. Considering at least one of the species of bacteria chomping on the particulate plastic occupies the same genus as one that causes cholera, no one wants to make any rash decisions. For the plastic that remains solely on land, students from Yale University’s Rainforest Expedition and Laboratory discovered a fungus in the Amazon in 2012 that likes to dine on polyurethane without the need for oxygen. Adding a heap of plastic into a strictly controlled digester along with Pestalotiopsis microspora may one day be a way to reduce the amount of plastic reaching the ocean from land.

How You Can Take Part

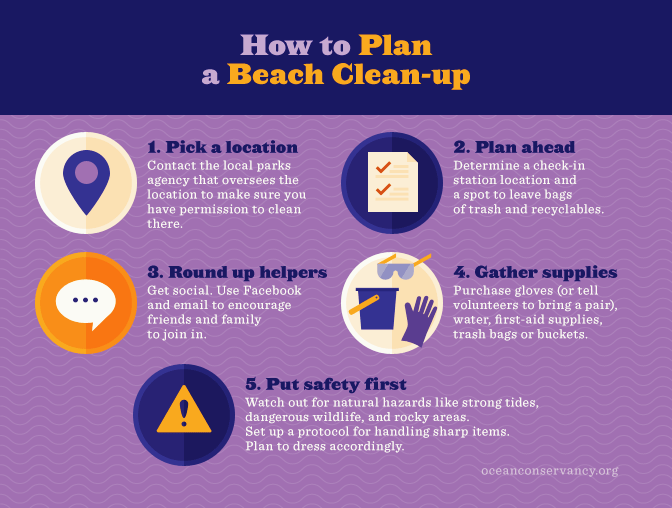

On a smaller scale, communities can do their part by organizing beach cleanups and switching from petrochemical plastics to organic-based alternatives. Simple changes in everyday habits, such as swapping plastic water bottles for reusable containers and opting for cloth bags instead of flimsy carryout sacks, would make a sizable dent in reducing the trash reaching our waterways. Choosing personal care products that do not contain tiny plastic scrubbing beads or seeking out packaging made from a percentage of recycled material help send a message to corporations: The health of the environment and human safety are important factors consumers are prepared to pay a little extra for. Contributing to non-profits such as the All One OceanCampaign, Annie Leonard’s The Story of Stuff, and 5gyres.org expands efforts to spread awareness, mobilize citizens, and establish lobbying interests with enough power to influence legislation. Like climate change or air pollution, removing the plastic from the planet’s oceans will involve stakeholders that occupy positions in government, media, and the scientific community. Although the immensity of the situation may seem overwhelming at first, it is possible for a species clever enough to engineer such feats of chemistry to also help deal with its consequences.

Source: Fix.com